Interview by: Zoe Presnal

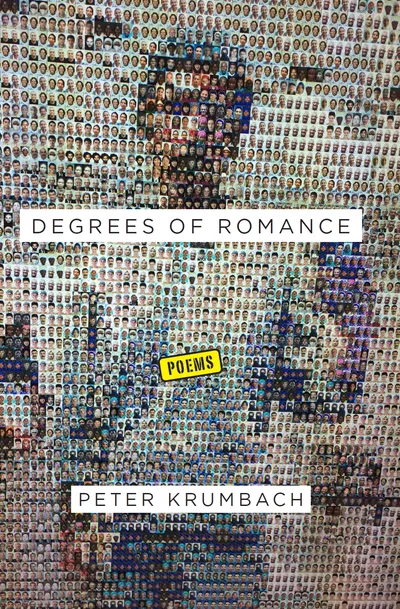

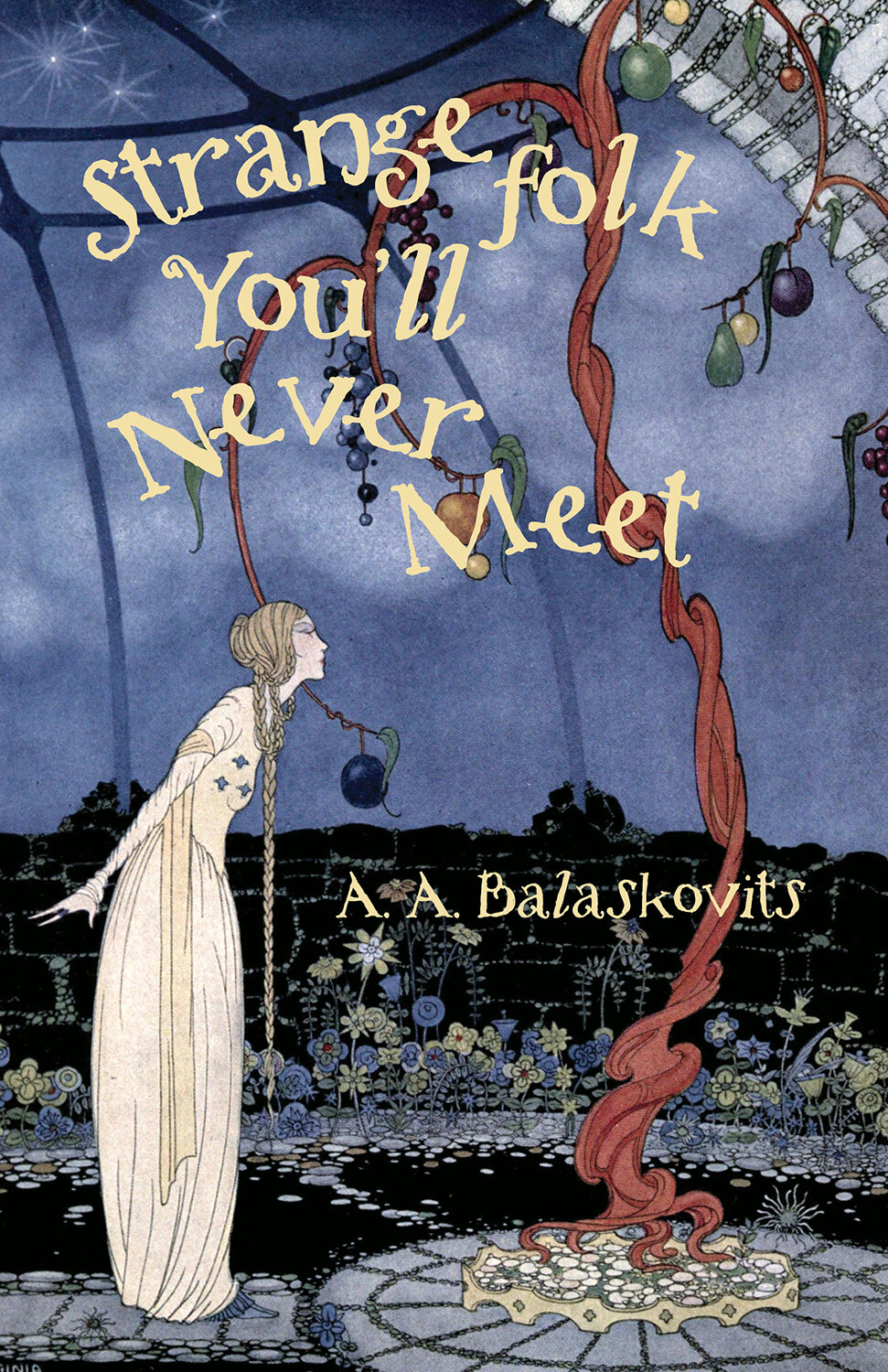

A.A. Balaskovits is the author of the short story collections Magic for Unlucky Girls and Strange Folk You’ll Never Meet. Strange Folk You’ll Never Meet is a collection of captivating contemporary fantasy and folk stories. In this interview, we discussed Balaskovits’s writing process and inspirations for Strange Folk You’ll Never Meet.

Zoe Presnal (ZP): What was your process like for writing and organizing this collection? Were there any other stories that you considered including but ultimately decided not to? If so, why?

A.A. Balaskovits (AAB): Many of the stories in Strange Folk are short-shorts, or stories less than 1,000 words long, so a lot of the process was almost experimental: limiting myself to that word count. It did make the ordering of this collection challenging, as a handful of these stories are extremely long (“The Mad Monks Weeping Daughter,” “Strange Folk,” “The Skins of Strange Animals”) and I had to make peace with having the “tall man” and “short man” next to one another. I do worry that it creates a sort of whiplash for the reader, but perhaps it is a relief, as well? I adore short-shorts, how they come in, stab you in the belly, and then leave. Robert Hass’ “A Story About the Body” is one of my favorite pieces of writing. It’s so concise, so perfect, so devastating. I’m currently writing a far-too-many-words-already novel, and I must constantly remind myself of the lessons I learned while writing this collection (and which I am failing at): say more with less.

Funnily enough, a handful of the stories in this collection were the ones cut from my first book, Magic for Unlucky Girls. The last story, “A Girl, A Bird, A Rocket to the Moon” was originally written for that collection, but it didn’t fit in tone-wise with the rest of the stories. It may not fit in with the rest of Strange Folk either, but I wanted to end this collection on a less devastating note. Not to say it’s a peppy, happy story by any means, but it’s less awful than “Mama Floriculture,” a tale of a woman who keeps snipping off parts of her babies.

ZP: What, if any, stories/folktales from your life inspired you to write your own fantasy? What inspires you to add your own twists on classic fairytales?

AAB: The stories about adoption—“Home Belly Wants” and “A Tale of Two Adoptions”—are directly inspired from my own. I am adopted, and my sister is as well. Most fairy tales don’t cover this topic, and certainly none of the famous ones, and if they do it’s the tale of the changeling, from the perspective of the parents, and seen as a disaster. Fairy tales tend to be obsessed with the “true” child, or “true” mother, or “true” princess (The Princess and the Pea), though truth is a complex affair. The traditional literature on the subject, geared usually towards the adoptee or adoptive parents, is full of how the child was “chosen,” given up by the birth parents (who usually have little to no role in the text; they disappear, as though they were cuckoos) and gifted a warm, loving home. The reality is far more nuanced.

Adoption is an incredibly tenuous subject, which I believe we are only now beginning a cultural reckoning with, as adoptees are beginning to be given a platform to express the complexities of this practice—see The Rumpus and their Adoptee Awareness archive. My experience was a delightfully positive one, but I have known plenty of other adoptees to know mine is the exception, not the rule. I want to read fairy tales about adoption, told by adoptees. I want them to be as messy as the reality.

I have come to believe that fairy tales are stories of political violence. I was first inspired, as is everyone who reads her, by Angela Carter. The Bloody Chamber opened up a venue of literary discourse I had not realized was still being utilized. Fairy tales are often relegated to children’s literature, thanks in part to Disney in today’s age, but they are also tales of power: they inform behaviors, dictate what is good or evil, and (usually) end quite happily, a merry justification for any suffering the characters experienced. I’m not the first to revision fairy tales and I will not be the last. These tales endure in part because they are simple guides on how to live a “moral” life, but they are also minaciously malleable. Kate Bernheimer identifies the four elements of fairy tales in “Fairy Tale is Form, Form is Fairy Tale:” normalized magic, intuitive logic, abstractness and, crucially, flatness. This flatness of these characters means that any artist who reimagines them puts their own biases, anxieties, and desires into these characters.

ZP: You use names like “the mother” or “the grandmother” in many of your stories. How does using feminine nouns further the identities of your characters? What’s your vision for conveying the characters in your stories as roles rather than with names?

AAB: My first instinct for this answer is pure laziness. But when I think about it, my first instinct is informed by my second instinct: people are often defined by their roles. Every company I have worked for, I almost never know the names of the higher ups—they are the CEO, the President, the Dean, the Boss, etc. Similarly, I didn’t know my mother’s or grandmother’s names until I was older.

It’s a convenient shorthand to call someone by their title as opposed to their name. Names can tell us a little bit about a person, but a role or a title comes with assumptions about who they are. The CEO is a leader. Mother or Mom or Grandma is typically considered a warm, caring, giving, feminine person— The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein is, perhaps, the pinnacle of this depiction in literature. I enjoy playing with those assumptions. Not every mother is warm, or caring, or giving, or feminine. Not every grandmother is a font of wisdom. But they are all people, and people are messy folk.

ZP: On a similar note, I really loved how a lot of these tales use themes of womanhood, motherhood, and childhood. What inspires you to write about the experiences of womanhood and motherhood? What’s the significance of illustrating women with “missing” parts of themselves (“A Woman With No Arms,” “Get Bent,” “An Old Woman with Silver Hands,” etc.)? What else about the image of motherhood/birthing in general intrigues or inspires you to write?

AAB: This is a lovely question, thank you! I write about womanhood and, by default, motherhood, a lot. Every story of mine that involves motherhood is aching towards that ultimate anxiety of mine, that I will become a mother. I have no desire for it—I have never had a desire for that responsibility and control over another person—but society certainly has that desire for me and other people who can conceive. Elon Musk is currently leading that call, but so did Nicolae Ceaușescu, and so does the Quiverfull movement, and every politician who is currently anxious about abortion access and birth control in this country and beyond. I am inspired by the historical place I occupy, and others like me, as a person who can create life in my belly, and equally inspired by how that gift has been used to punish, to injure, and to control people like me.

Birth is a process I consider absolutely miraculous and horrific in equal turn. One utilizes the same muscles to bring a child into the world as one does to take a shit, and often one does defecate on the birthing table, or pool, or wherever one decides to do it, or is decided for them to do it—in America, that sometimes means in handcuffs, if you are unfortunate enough to give birth in prison. After the birth, the body continues to bleed and bleed and bleed, while the baby cries, letting you know they are alive, alive, alive. Beauty and the grotesque are bedmates, and I think it does a disservice to separate them.

As for the stories that have ladies and missing parts—the series that begins with “A Woman With No Arms” and continues into two other tales is based on “The Girl Without Hands,” a lovely tale found in the Grimms’ collection (and others) about a woman who escapes an evil wizard by cutting off her hands and crying over them (I guess wizards aren’t into that) and then she does some wild things with her neck. A lot of my work deals with body horror in some way, which is not strange considering the medium—fairy tales have countless examples of this. For these women, in my stories, and “Get Bent” in particular, it is less about the “horror” of missing a part of you, but how you bend to overcome what was taken or given up.

There’s a lot of graphic and violent imagery in your tales. Do you find it difficult to write gore in vivid detail? What’s your process for working through violent imagery? What do you want a reader to feel or take from these images?

It is natural for me to write about gore and violence; how awful is that? I watch an obscene amount of horror movies, and I was part of the early internet, so shock websites like rotten.com and their ilk were ones I looked at. My process is witnessing it in some manner, in some form. For my novel, one scene involves slaughtering a pig, so I watched countless videos of that practice, from cutting its pink throat to hanging it up to bleed out, pouring boiling water over its skin, and sticking a sharpened pole up its rectum and through its snout to hang the carcass over a fire, waiting for the flesh to tighten and crisp. I don’t watch everything—I read a far lot more, but even I have limits and make do with my imagination.

However, violence and gore are everywhere. We’re living in an age where we can livestream genocide, a thing I once believed we all agreed was bad. Why would I write about people except as we are? We are a violent people and a violent species. Glorious experiment though it is, the entire internet is rotten.com. And we, the people, are the internet. I don’t think that this is necessarily a bad thing. It is a mirror. What another person does, I too am capable of; kindness or cruelty, or something in-between. That’s a part of who I am, and who you are, a capability to go either way, held back only by choice and circumstance.

The way I see it, when we tear one another open, as we are often inclined to do, there’s a lot of squishy, gross stuff inside. We all share this. We all take a shit, too, so why is putting that on the page distasteful? It is a great unifier, in birth, in death, and ideally several times in-between. Nothing the body can do or has inside of it feels off-limits in art.

As to what I would want from a reader: ultimately, it is up to them what they take from my writing. Once you put it out into the world, it is no longer yours, and the reader can do or not do whatever they feel like. For some, that is to get sick to their stomach, and I understand that. I’m sickened, too.

A.A. BALASKOVITS is the author of Strange Folk You’ll Never Meet and Magic for Unlucky Girls. Winner of the grand prize at the Santa Fe Writer’s Project’s literary awards, her work has been featured in The Journal, The Kenyon Review Online, minnesota review, Best Small Fictions and many others. She currently resides in Chicago. Find her at aabalaskovits.com.

ZOE PRESNAL is a Creative Writing student at Western Michigan University. With an editorial internship at Third Coast Magazine under her belt, she feels more than ready to work when it comes to uplifting fellow writers. After graduation, Zoe plans to use her BA to further her work in publishing and editing. When she’s not reading or studying, Zoe enjoys scriptwriting and honing the craft of on-screen storytelling.