Recommended Books

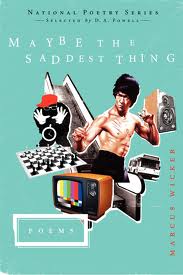

Maybe the Saddest Thing by Marcus Wicker

(Harper Perennial: 2012. 79 pages.)

Reviewed by Nick Ripatrazone

“How does one finesse canon?” So wonders a narrator in Maybe the Saddest Thing, the debut collection by Marcus Wicker. The book is an extended answer to that question, but that response is played back with the care and control of a tight beat. Wicker’s book engages Pam Grier, Baywatch, 70s kung fu films, and other popular culture miscellany, yet does so in a more useful manner than most poets, who choose to undermine such culture for convenient and ephemeral irony. Wicker’s narrators are the cores of this show, and they educate the reader about how those cultural images and sounds form and reform personas.

Wicker’s control of these poems begins with his usage of tone, and ends with the earned confidence that the material of these poems can accumulate into questions rather than conclusions. That previous question, “how does one finesse canon,” is posed after the narrator thinks about a scene from Finding Forrester “when the brown jock uprooted from the Bronx / beats his teacher at literary charades.” In the film, the “Scottish mentor” saves the student from allegations of plagiarism, but Wicker’s concern is deeper: “You’re probably thinking this is about white men. / About gold-encrusted measuring sticks.” The narrator is “stumped about whose brother I be.” Who was gaming whom: the racist teacher, the mentor, the student? Or was it the poet, who seems to know the originating art was oversimplified itself, referring to it only as “that movie,” never by name?

The genesis of these questions are considerations of poetic narration, and form Maybe the Saddest Thing’s highest achievement: an original contribution to the trope of naming in poetry. The trope of naming in poetry is never far from the act of ars poetica: process and creation are wedded to identity. The tightly wound, sprung rhythms of Gerard Manley Hopkins often focused on locating the poet within the poetic creation. Hopkins’s final sonnet, “To R.B.”, momentarily dislocates the poet from the poetic act by addressing the lament toward the initialed recipient—Robert Bridges, the posthumous collector and publisher of Hopkins’s work—but then returns the actions insular, appropriating a birthing metaphor that concludes with an apology to the poem’s recipient. The apology is one of poor art, inadequate poetry, and yet the apology is as much one of incomplete identity. If the poem is not finished, neither is the poet.

The thrust of much later, specifically American insular poetry drifted toward the confessional, where the particulars of naming and renaming have been devalued in comparison with the immediacy of experience. Self-criticism is replaced with self-contemplation. Such experiential work tends to be longer, layered further from the named subject; John Ashbery’s “Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror” buries the self beneath allusion and sheer length of the work. More contemporary moments of poetic naming are comfortable with direct play, and in their abbreviations foster a link with the consistent tradition of naming within hip hop. For such a trope of naming to exist in the lyrics of hip hop is no surprise; rather, an almost necessary and appropriate evolution from the form and context of the art. By placing importance on performance, spectacle, and artist identity beyond the art, the aesthetics of hip hop are inevitably grounded in similar naming. Names are often the first aspect of an artist’s identity that the audience learns, and those names are used for differentiation, for bragging and bargaining, and for affirmations of masculinity and femininity.

An essential consideration is whether the trope of naming in hip hop—so firmly established in that art’s format of spectacle, recording, and even battle, as well as a necessary technique to establish credibility and singular identity—is in any way congruous with the trope of naming in non-musical, non hip hop influenced poetry. Two major connections exist. First, that the trope of naming in hip hop is a linguistic cousin to the peculiarly American, Whitmanesque songs of self; second, that hip hop has both influenced and been influenced by the black tradition of revisionist persona poetry, exemplified by the work of Tyehimba Jess and Frank X Walker.

The connection with Whitman’s “Song of Myself” is primarily one of ethos, the self-celebration whenever one “sing[s].” Besides making the self-subject the center of communication—“trippers and askers surround me”—Whitman fabricates the heightened narrative of myth. Jess and Walker share Whitman’s breadth in constructing entire collections focused on particular personas, but the essential difference is the positioning of those personas in response to greater concerns of blackness. For both Jess and Walker, black narratives progress from a near-oral state to performance, ultimately in jazz and blues, and later, it could be extrapolated, in the varieties of hip hop.

Yet Wicker’s debut is essentially different from the work of Jess and Walker, who chose to refigure, and therefore take back, black historical figures. Frank X Walker’s sequenced collections—Buffalo Dance: The Journey of York and When Winter Come: The Ascension of York—provide voice to York, William Clark’s manservant during the Jefferson-dictated exploration to the Pacific. If Walker shows the work necessary to rename one who has been lost, then Tyehimba Jess’s Leadbelly positions music as the activity in which the black artist may react to the white manager, or more specifically, the white folklorist who hopes to present Leadbelly as a “discovery.” Leadbelly contains both lineated and prose poems, persona and personified poems, all with an intense central focus on a representation of Huddie Ledbetter. Unlike Walker’s York, who did not produce any artistic testament to his life, Jess’s subject already has a “name” through his recordings and legend, making Jess’s endeavor even more difficult.

Wicker is similarly concerned with representations of race, but his approaches toward naming exists on an impressively wide scope, and are focused on a malleable contemporary narrator rather than a single historical figure. “Self Dialogue with Marcus,” like Hopkins and Ashbery, opens his narrator’s concerns beyond the self, yet Wicker’s approach allows him to yoke the projected identities back toward his own. The poem begins “In every movie there’s a snaggletooth thug who pimps broken / speech or a snob poodle who shits for a living named Marcus,” pausing his name until the cinematic caricatures have been presented. “Fuck every Marcus,” Wicker continues, knowing full well the poet himself is implicated in the litany. Wicker presents Marcus Garvey, Marcus Aurelius, the town Marcus, Iowa, and more, concluding that “the Marcus for this Marcus is most certainly Marcus.” Wicker’s play resides in his humor; names, in this poem, are both malleable in terms of context and yet collective, in that each Marcus is connected.

Wicker’s narrators implicitly tie concerns over naming with expectations of race and masculinity. Thankfully, he returns to his trend of stirring thought rather than forcing conclusions. In one of the collection’s few prose poems, when the narrator’s father “found Kenny G lying on my nightstand” he learned how “a black father can and will enter a bedroom” and “drag the boy out of bed down two flights of stairs and toss him in front of a turntable.” The narrator stands before his father’s “wall of LPs” and is warned: “you better not scratch my shit.” Though he started this day with Kenny G, “bad perm and all,” now

Eric Dolphy squeals, leaps, and dives inside my abdomen. Roy Ayers kneads and vibrates my chest. Freddie Hubbard’s wail could crack glass, my ribs. Pharoah Sanders shivers all over my face. Every wax-gash, knick, and hiss. Every cut. Every record pierces skin.

When his father finally returns to the basement, the narrator is crying “because I’ve been down here forever.” The line is powerfully ambiguous: he has been downstairs since before breakfast, but he’s also always “been down here” because of his born identity.

The expectations continue in “1998,” where the narrator, “head / caught between middle / & high, private & public / school,” is “[blowing] / smoke through bull nostrils” when he hears that “Rodney was talking reckless / about my younger brother.” The narrator interrupts his own memory of the culminating fight in a park:

I can’t go on talking

to you this way

any longer. All this time

I’ve been working up

to say something about

that liminal place between

manhood & cartoon-

cool.

That complicated tone returns with equal parts humor and seriousness in the book’s sequence of love letters to celebrities. “Love Letter to RuPaul” begins with a confession:

You have one of the longest,

thickest, most veined, colossal

set of hands that I have ever seen

and, frankly, they cast a spell on me.

That admission comes from “a black man who has never worn pink—/ not a polo to a country club” who is nonetheless “ravished” by “one of my earliest memories”: “you are wearing / a pink sequined dress, endorsing a hamburger.” This love letter is one of appreciation of honesty: “How / raw you must be. To sit before a camera, / legs uncrossed.”

That same appreciation ends “Love Letter to Justin Timberlake”:

Do you remember the Super Bowl?

How you tore Janet Jackson’s breast

from her top?

I love you that way.

Her earth-brown bounty of flesh—

large, black nipple

pierced, wind chapped, hardened.

And you saying. Go ahead. Look.

For Wicker, the act of naming is the act of poetry, and that poetic act is wedded to performance. Maybe the Saddest Thing shows that a talented poet is not “flattering myself” when engaging in the act of naming: he is contributing to a poetic and artistic tradition, as in “The Break Beat Break.” The final poem of the collection springs forward from “that faithful kick drum ride cymbal solo pattern / that never fails to unlock a host of holy ghosts / in any B-boy with a pulse.” That break “comes from you,” and is “part of our collective audio unconscious.” Maybe the Saddest Thing, a book concerned with the complexity of poetic naming, ends with a poem looking outward toward the second person. This narrator is correct that when “the break starts… dancing never felt so motherfucking right.” The same could also be said of poetry.

***

Marcus Wicker is the author of Maybe the Saddest Thing, selected by DA Powell for the National Poetry Series. The recipient of a 2011 Ruth Lilly Fellowship, he has also held fellowships from Cave Canem, the Fine Arts Work Center, and Indiana University where he received his MFA. Wicker’s work has appeared or is forthcoming in Poetry, American Poetry Review, Third Coast, and Ninth Letter, among other journals. Marcus is assistant professor of English at University of Southern Indiana and poetry editor of Southern Indiana Review.

Nick Ripatrazone is the author of two books of poetry, Oblations and This Is Not About Birds (Gold Wake Press 2012) and a forthcoming book of non-fiction, The Fine Delight (Cascade Books 2013). His fiction has appeared in Esquire and The Kenyon Review, and has received honors from ESPN: The Magazine.